1852 words | 7-minute read

Naval Tata's life had space for big business, labour relations, sports administration, charity endeavours and a load of laughs. His heart had room for all that is good about human nature.

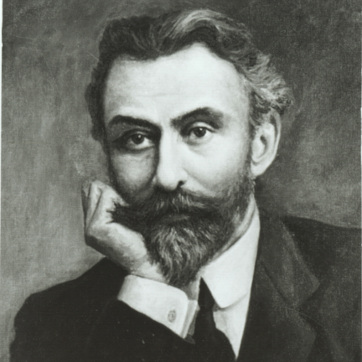

The god of kindness must have played midwife when Naval Hormusji Tata was born on an August day in 1904. Over the next 85 years, across a life that embraced big business, labour relations, sports administration and charity endeavours, Naval struck a chord of benignity with all whom destiny paced in his path. Bar a roaring sense of humour, everything about him was enveloped in a gentle wind of humility, sympathy and tolerance.

Naval was as much the public face of the Tatas as JRD Tata. Born in the same year, their professional careers followed parallel lines. They shared a passion for the group and an unwavering commitment to its ideals. Personally, though, they were quite different. Where JRD was a somewhat reserved and shy figure, short of fuse in the face of foolishness and pretension, Naval was a gregarious soul who could get along with all manner of people, as forgiving of human frailties as he was accepting of life's vicissitudes.

The group and the family represented two sides of the same coin for Naval, who considered them inseparable entities wedded to a virtuous cause. He had empathy for the poor that probably sprung from a childhood shorn of privilege. Naval, who lost his father as a kid, was studying at an orphanage when he was adopted, at age 13, by Lady Ratan Tata, the wife of Sir Ratan Tata, the second of Jamsetji Tata's two sons (Lady Tata was apparently bowled over when Naval, spiffed up in a sailor's suit, saluted her at their first meeting).

Naval would say of his adoption that it was as if someone had waved a magic wand and a fairy godmother had appeared. "I am grateful to God for giving me an opportunity to experience the pangs of poverty, which, more than anything else, moulded my character," he once averred.

Keeper Of The Flame

Providence may have played a part in catapulting Naval to affluence, but his achievements owed nothing to chance. He graduated from Bombay University and did an accounting course in England before joining the Tata Group in 1930. Three years later he was made secretary of its aviation department. He was appointed the managing director of the group's textile companies in 1939 and became a director of Tata Sons, the core enterprise of the conglomerate, in 1941. He was appointed chairman of Tata Electric Companies (now Tata Power) in 1961 and Deputy Chairman of Tata Sons a year later.

Beyond the business sphere, Naval was closely associated with the Tata charities and served as chairman of the Sir Ratan Tata Trust from 1965 to the time of his passing. Besides, he was the chairman of the Indian Cancer Society from its inception in 1951 right up to 1989. Naval proved his mettle as a sports administrator during an outstanding stint as president of the Indian Hockey Federation from 1946 to 1961. He was the first president of the All India Council for Sports and also served as vice chairman of the International Hockey Federation, the game's governing body, for more than a decade.

Champion Of Labour

Naval's most valuable contribution outside of business, though, was in the domain of labour relations. For more than four decades he provided a voice of reason, consideration and conciliation to national and international organisations working to reduce and resolve employer-employee frictions. This was period, especially in India, during which relations between workers and their managements were corrupted by political and economic factors. Naval's inherent honesty, his concern for the working class, and his ability to bridge diverse points of view helped diffuse many volatile situations, while bringing clarity to issues of universal importance.

Naval's first serious brush with labour relations as a subject outside the factory floor happened in 1946, when he was nominated to represent the Indian textile industry at a meeting of the Geneva-based International Labour Organisation (ILO). He became a part of the ILO's governing body in 1951 and continued in the post till his demise in 1989. He was a member of the International Organisation of Employers, also based in Geneva, for 38 years and was the president of the Employers' Federation of India from 1959 to 1985. Naval was the driving force behind the setting up of the National Institute of Labour Management (now known as the National Institute of Personnel Management), serving as its president from 1951 to 1980.

In an industrial climate vitiated by seriously flawed political philosophies, undermined by a governmental outlook that saw the entire entrepreneurial class as exploiters, and compromised by lopsided laws that encouraged irresponsible trade unionism, Naval worked overtime to mend and heal. It was an exceptional task, and ordinarily one that would have been made more difficult by Naval's own credentials as a scion of one of India's foremost business families. That his lineage and position did not become a liability can be put down to Naval's remarkable qualities as a human being.

"He had this tremendous capacity to gel with people from different walks of life," recalls well-known industrialist Keshub Mahindra. "Naval believed in responsible negotiations between employers, workers and governments in the common search for equitable solutions. He was probably the only businessman that labour respected and had confidence in. Part of this was due to his ability to get along with them, but it also had something to do with the fact that he was a superb listener." Naval was an employer who always regarded himself as a trustee of the rights and interests of workers, especially those in the unorganised sector.

Like JRD, Naval had an essential decency that was immediately visible even to those who had only a passing acquaintance with him. There wasn't a trace of arrogance in him, which explains why he could relate so easily to workers. He would bond with them through anecdotes and stories, some of which he made up as he went along. One of his favourites went thus: A supervisor finds one of his shop-floor workers missing from his station for close to an hour. "Where have you been?" he asks the man when he saunters in at last. "Sir, I went for a haircut," the worker replies. "You went to cut your hair on my time?" the livid supervisor thunders. "What to do, sir, it grew on your time."

Apart from a raconteur's knack of telling a telling tale, Naval possessed, in the words of one of his friends, "an unstoppable sense of humour". He unleashed this gift on all occasions and in every sort of company; the more stuffy the gathering, the more likely Naval would unload a gem.

He also had formidable diplomatic skills. Old hands at the ILO remember Naval's calming influence and wisdom as being crucial in preventing many a potentially damaging situation from coming to a head. Naval's ILO innings roughly coincided with the Cold War era, which pitted the erstwhile Soviet bloc against the so-called free world. India and, by extension, its representatives on bodies such as the ILO — Naval and people like him — had to frequently walk a delicate line in matters of policy and their formulation. Naval emerged from these confrontations with his reputation enhanced. He brought the same set of skills to the table in his capacity as a representative of the Tatas while negotiating with the government in the 'permit raj' age of perennial controls and regulations.

India's Olympic Pride

Indian hockey was another beneficiary of Naval's capabilities. He was the administrative head of the game in India when the country won gold in three successive Olympics. India's participation in the first of these, the London Olympics of 1948, was in doubt till the last minute for financial reasons. Naval met Jawaharlal Nehru and somehow convinced him that it was in newly independent India's interest to have her hockey team take on the world.

Nehru's backing ensured the team's passage to London, but the prime minister, like many Indians then, appears to have been spoiled in later years by the continuous success of the country's hockey heroes. After India had retained the gold at the Helsinki Games in 1952 through a narrow 1-0 victory over Pakistan, Nehru expressed his disappointment to Naval at the team not having won by a 'tennis score'! "Naval, is our standard going down?" he asked. "No, sir," Naval replied, "the standard of other countries is going up." Talk about portends of the future.

This wonderful stretch of success, powered by players such as RS Gentle and Leslie Claudius, was in some part thanks to the support guaranteed to Indian sport by the Tata Sports Club, which Naval nursed with affection and competence for close to 50 years. His espousal of the cause of Indian sport, through the Club and similar forums, helped a host of Indian athletes realise their dreams.

Between his love of sports, his obligations in labour relations and his responsibilities as a business leader, Naval squeezed in time for a one-off excursion into mainstream politics, contesting as an independent in the Lok Sabha elections of 1971. The constituency was Bombay South and his competition included George Fernandes, who had wrested the seat from the redoubtable SK Patil in the previous election, and NN Kailas of the Indira Congress. The media had a field day as Fernandes, dubbed the giant-killer after his stunning victory over Patil, and Naval, 'the giant of industry', slugged it out, with all the masala of a high-profile Indian election to spice up the battle.

In the event, both were thumped by Kailas, a one-time wonder who coasted home the winner on the 'Indira wave' let loose by the Bangladesh war. Naval, who finished a credible third, had set out on the political path to prove that honest people could and should contest elections. He made his point, but he obviously did not relish the experience enough to have another go at political campaigning.

Electricity-generation held much more allure for Naval than electioneering. Under his stewardship Tata Power increased its capacities and reach, despite being entangled in bureaucratic delays of multiple kinds. His unstinting determination held the key to the company's expansion in India and, in a limited way, abroad. The efficiency and reliability factor now taken for granted by Tata Power consumers in Bombay owes a lot to Naval's vision and his pursuit of business excellence.

Naval symbolised all that is best of the Tata spirit of giving back to society and the communities in which its enterprises grow. His caring and endearing nature, his abiding concern for those as poor as he once was, his love of a good laugh, and his instinct to trust even those not worthy of it made him one of a kind. If the Tata story is ever told from the heart, he will rank among the most loved of them all.