March 2025 | 1839 words | 8-minute read

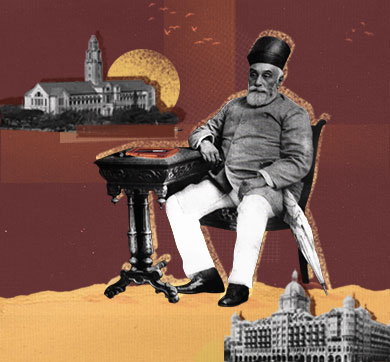

Jamsetji Tata made a careful study of the labour problem, maturing, by steady stages, a scheme for the welfare of the workers. From the first moment his aim was to establish a model mill, and at length, by care, labour, and thought, he succeeded." An excerpt from his biography:

As soon as he had disposed of the Alexandra Mill, he mapped out that prosperous concern which enabled him to lay a stable foundation for the remainder of his enterprises. After his tour in the Middle East, and his visit to England, he settled down to work.

A suggestion, made by his father, led him towards an undeveloped district. The manufacturer in Western India was imbued with the idea that Bombay, and Bombay alone, was the proper centre for development, but the city was remote from the districts in which cotton was grown, and Mr Tata decided to locate his mills within easy reach of the raw material, in the neighbourhood of a profitable market, and in an area where supplies of both coal and water were accessible.

With patience and thoroughness he journeyed through the likelier parts of the peninsula in order to find a site which would meet his requirements. After careful investigation he fixed upon Jubbulpore (now Jabalpur), in the extreme north of the Central Provinces. He was attracted thither by the prospect of utilizing hydraulic power in the working of his mills. The falls of the Nerbudda (Narmada) River would have served his purpose.

When he had selected the site, he applied to the Government for the necessary concessions, but found that his choice was obstructed by one of those curious impediments which dog the steps of a pioneer who attempts to modernize the East. At the chosen place a fakir had established a small shrine, the sacred resort of pilgrims from the surrounding districts. The fear of a religious riot, if the holy man were evicted, led to an official refusal of the concession. Mr Tata was obliged to turn his steps elsewhere, but the idea of water-power took root in his brain. Twenty years later, when electricity had come into its own, he threw himself with ardour into a scheme for driving the mills of Bombay by combined electric and hydraulic energy.

Towards Nagpur

His methodical mind had prepared an alternative site, and he next surveyed Nagpur, in the Central Provinces, some five hundred miles from Bombay. Here again Mr Tata’s requirements were fulfilled. The town was situated in a cotton-growing district; it was the terminus of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway; it was within reach of supplies of coal from the Warora mines, and it was the chief market for many miles round. It was also the centre of a large hand-loom industry, ready for the products of Mr Tata’s spinning-sheds. There were, however, many obstacles to overcome. Though hand-spinning and weaving had for long flourished in the district as a cottage industry, and a certain amount of labour was to be had, the local labourer had no experience of organization. The roads were bad, and furnished but a poor surface for those bullock-carts which provided the only means of transport to the neighbouring settlements.

When Mr Tata first announced his intention of building a mill in what seemed a remote and backward town, the people of Bombay laughed him to scorn for ignoring the place which they regarded as the ‘Cottonopolis’ of India. But Jamsetji Tata knew his business. Land in Nagpur was cheap, agricultural produce was abundant, and distribution could easily be facilitated, owing to the central position of the town and the gradual growth of converging railways.

When Mr Tata first announced his intention of building a mill in what seemed a remote and backward town, the people of Bombay laughed him to scorn for ignoring the place which they regarded as the ‘Cottonopolis’ of India. But Jamsetji Tata knew his business

After a lengthy search for a site, Mr Tata purchased, for a comparatively small sum, ten acres from the Rajah of Nagpur. The site was close to the railway station, and to the ‘Jumma Talao’, a reservoir, excavated in the eighteenth century. The earth taken out had been dumped at the side of the tank, forming a number of mounds which had to be removed. In a country where unskilled labour was cheap, Mr Tata took the risk of converting the marshy tract into a stable foundation. The soil which his men transferred from the mounds was used to level the whole space. Some people in Nagpur shook their heads at this fantastic operation. A local Marwari banker, who was asked to subscribe for shares, refused to participate in the schemes of a man who, as he said, was putting gold into the ground by spending money upon the filling up of swamps. He lived to vary his phrase; and was fain to confess ‘that Mr Tata had not put gold into the ground, but had put in earth, and had taken out gold’.

Leading hands-on

Those who doubted the wisdom of the new project—and there were many who lived to regret that they had not purchased shares—hardly realized that India had given birth to a future captain of industry. Later in life Jamsetji Tata delegated his work to others, and was content to inspire their efforts, but the mills at Nagpur were the work of his own hands. From the first he took up his residence in the town. In 1874 he began, in conjunction with his father and a few friends, to promote the Company, which was formed and registered in Bombay, under the title of the ‘Central India Spinning, Weaving and Manufacturing Company, Limited’. The original capital, furnished by quite a small number of subscribers, amounted to Rs 15,00,000 in 3,000 shares of Rs 500 each. Mr Tata’s remuneration as Managing Director was fixed at Rs 6,000 a year. It was but a meagre sum when one remembers that he had to keep up a second house and to travel to and fro between Nagpur and Bombay. When he finally gave up his residence near the mills, he reduced his salary to Rs 2,000 for the benefit of the shareholders. They, indeed, had cause to be grateful. He brought to bear upon the new enterprise his practical knowledge, which was the result, not only of careful observation, but of the experience gained at the Alexandra Mill.

Early and late, with untiring energy, he supervised builders, inspected machines, tested material, or checked returns. He embarked on his enterprise with courage and conviction. He was a pioneer, not only in his choice of a new locality, not only in founding the first joint-stock company in that part of India, but in his efforts to build up an organization which, as far as his firm and his country were concerned, ultimately proved a model to his successors and to his fellow mill-owners.

Eye for talent

For several years Mr Tata remained at Nagpur, and gave the whole of his time to the solution of those problems which face the man who sets out to build a mill on a marsh. His keen eye for the discovery of efficient helpers soon gave him an excellent right-hand man. He told his friends that he was on the look-out for someone, with common-sense, honesty, and intelligence, whom he could train according to his own ideas. Among those who attracted his attention was a young Parsee, Bezonji Dadabhai Mehta, a Goods Superintendent on the Great Indian Peninsula Railway.14 Though Mr Bezonji knew nothing of the cotton industry, he had considerable experience in organization, and possessed those qualities of character which appealed to the elder man. In 1876 Mr Tata took him into his employment, and, after two years’ training, installed him as manager of the new Company. Some time later he was equally astute in his choice of an expert, Mr James Brooksby, an Englishman who combined abundant energy with the requisite technical knowledge. Both these men speedily justified their selection, and Mr Tata was the first to admit how much his new venture owed to their ability and care.

Early and late, with untiring energy, he supervised builders, inspected machines, tested material, or checked returns. He embarked on his enterprise with courage and conviction

On 1 January 1877, the day on which Queen Victoria was formally proclaimed as Empress of India, the mills were opened, and in order to associate his enterprise with this notable occasion, Mr Tata named his factory the Empress Mills. They were equipped with 15,552 throstles, 14,400 mule spindles, and 450 looms. The motive power was derived from a pair of compound engines capable of developing 800 i.h.p. The long low buildings which skirt the Jumma Talao were, from the outset, rendered capable of expansion. Their success has tended to obliterate all recollection of the difficult days which attend the launching of a new venture. Mr Tata spent many anxious months before he could work the mills to his entire satisfaction. Unfortunately, during his visit to England, he had been tempted to purchase an inferior class of machinery, selected with a view to conserving the capital of the new Company. He soon discovered his mistake. The quality of the yarn and the amount of the production were poor. The shares began to fall in the market and went down to half their nominal value. Without more ado, Mr Tata set out to redeem his error, for a fire which devastated the loom shed compelled him to renew some of his weaving equipment.

Relentless upgrades

In 1878 he was again in Europe. He spent a few days at the Paris Exhibition, and then, during a visit to England, he purchased a large amount of new plant. The instructions to his agent were revised. During his ownership of the Alexandra Mill, Mr Tata had employed a young Englishman, Jeremiah Lyon, to buy his machinery, and the two established a business connexion which outlasted the lives of both. Each regarded the other with the greatest respect. As a rule, Mr Lyon accompanied his employer to Lancashire, where they decided upon their purchases. This time Mr Tata made no mistake. He sacrificed economy in capital outlay to secure more efficient machinery. His policy was soon justified. In 1881 a dividend of 16 per cent was paid to the shareholders. As the mills began to earn money, a due proportion of the profit was set aside for depreciation. By degrees all the shops were refitted, and the cheaper machinery was relentlessly scrapped. He established a tradition, which his successors have preserved. The large amounts written off year by year for repairs and renewals have been more than justified by the excellence of the plant, and the consequent improvement of the production both in quality and quantity.

To ignore the difficulties of the initial stages would be to do Mr Tata a grave injustice. His personal supervision alone solved many a problem. He took heed of his errors, and obtained invaluable experience by traversing the whole maze of the cotton industry. He employed experts who carefully watched the machines, tested their output, and searched for improvements. He looked at his business as a whole. Year by year he planned new extensions. He planted gins and presses for the raw material within easy reach of Nagpur. Hampered at the outset by workmen of poor calibre, restless, casual, and inefficient, Mr Tata made a careful study of the labour problem, maturing, by steady stages, a scheme for the welfare of the workers. From the first moment his aim was to establish a model mill, and at length, by care, labour, and thought, he succeeded.

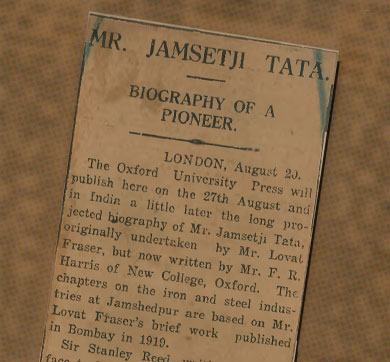

Excerpted from Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata: A Chronicle of His Life by Frank Harris.