July 2024 | 1660 words | 6-minute read

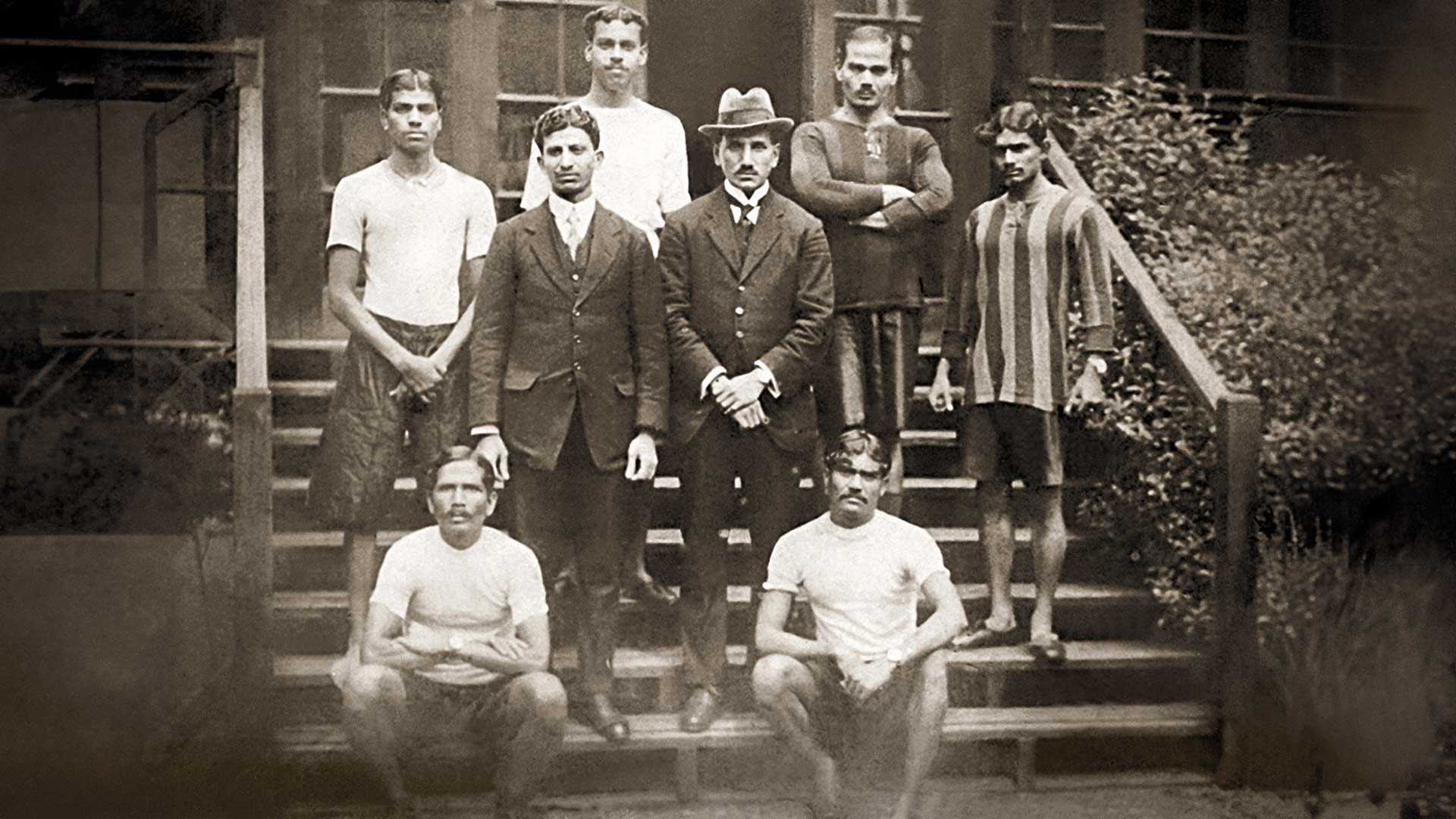

Over a 100 years ago, one man began advocating to send India to the Olympics. The nation had not even established its own Olympics association then, but that didn’t stop Sir Dorabji Tata. He put together a provisional committee and a contingent of four athletes and two wrestlers in time for the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp (began on August 14, 1920).

The 2020 Olympics in Tokyo marked the 100th year of India’s participation in the games.

The story goes that when Sir Dorabji returned to India after studying in England, he brought along a passion for “nearly every kind of English athletics” and the intent to introduce “a love for such things” in India. He did so by setting up high school athletics associations in numerous Bombay schools, which held sports meets that “embraced all the events that form part of the Inter-University contests every year in London”.

He was also elected president of the Deccan Gymkhana in Pune, and it was his presence at one of their sports events in 1919 that changed India’s sporting destiny.

That year, Sir Dorabji saw boys from rural communities, working in the fields and living off poor fare, run races ranging from 100-yard heats to over 25 miles (a full marathon covers a distance of 26.219 miles). He observed that some of their times were close to times clocked at the Olympics.

Sir Dorabji decided to send “three of the best runners” to the Antwerp Olympics to run the Olympic Marathon. “I hoped that with proper training and food under English trainers and coaches they might do credit to India,” he wrote to Count Baillet Latour, president of the International Olympic Committee, a decade later (1929). “This proposal fired the ambition of the nationalist element in that city to try and send a complete Olympic team.”

Veteran sports journalist Boria Majumdar wrote in The Economic Times, “India’s embrace of the Olympic movement in 1920, while still a British colony, was no mere coincidence. It was intricately linked to the forces of nationalism, the politics of self-respect and indeed the inculcation of what has been called the British ‘Games Ethic’ among Indian elites. Colonial India’s early Olympic encounter was born out of a complex interplay of all three factors, and it also forms a crucial missing link in the story of Indian nationhood. It was in Indian hockey, and in the Olympic Games, that the nationalist aspirations of colonial India found full expression.”

Paris, 1924: India’s first women Olympians

India also owes her next appearance at Olympics to Sir Dorabji. As a member of the International Olympic Association and president of the nascent Indian Olympic Council, he personally sponsored the larger Indian team’s participation in the 1924 games in Paris.

The team included India’s first woman Olympian, N Polley. She was part of the Indian tennis team, which made its Olympic debut that year.

It is also possible that Sir Dorabji’s wife, Lady Meherbai, was also part of the team. The age of an “M Tata” (45) in the 1924 Paris Olympics records matches her date of birth (October 10, 1879). According to the media guide of the London Olympics in 2012, M Tata and her partner Mohammed Saleem got a bye in the first round in Paris and conceded a walkover in the second round to Americans Vincent Richards and Marion Jessup, who went on to take the silver medal.

“But there’s some confusion here,” notes Stan Rayan of The Hindu. “While the ITF and 1924 Olympics tennis fixtures have given the Saleem-Tata pair a first-round bye, the mixed doubles entry list gives a ‘N part’ against her name. The Hindu’s 1924 July 17 edition, also has a mention of it, saying…In the third round of mixed doubles, Flaquer and Lili Alvarez walked over Saleem and Lady Tata (India) scratched. Did Tata pull out to allow Mohd Saleem to concentrate on his singles? Or was she unwell? Did the organisers stop her because she wanted to play in a saree? Was she around for the first round? It sure will be interesting to know.”

Amsterdam, 1928: India’s first gold

The period between the Paris and Amsterdam Olympics were crucial to the development of India’s Olympic prospects. It is during this period that the provisional All India Olympic Committee, formed ahead of the 1924 Olympics, made way for the Indian Olympic Association. The IOA was established in 1927 with financial support from Sir Dorabji, who also became the first president of the IOA. The expenses of the Indian Olympic Association in the initial stages, were also largely contributed by him.

As Peter Casey notes in The Greatest Company in the World? The Story of Tata, “He regularly scouted for sporting talent and established training clubs and facilities to develop it. The Willingdon Sports Club, the Parsi Gymkhana, the High Schools Athletic Association and the Bombay Presidency Olympic Games Association were all initiated by Dorab.”

The Amsterdam Olympics proved to be of historic significance for India. The Indian team consisted of seven athletes and 15 hockey players, and the Indian hockey team won the first Olympic gold medal for India. According to The Midland Daily Telegraph, India “during the whole of the Amsterdam tournament did not have a goal scored against them”!

5 more golds!

The Indian men’s hockey team remained undefeated for five more Olympics, settling for a silver for the first time in 1960 in Melbourne.

Interestingly, it was Sir Dorabji’s nephew, Naval Tata, who was the president of the Indian Hockey Federation when the Indian men’s hockey team won the Olympic gold in 1948, 1952 and 1956.

The book To Strive and To Soar documents how Naval Tata ensured that Indian hockey’s winning streak at the Olympics continued after independence. “Despite his best efforts, he had not succeeded in collecting the required amount and looking for an opportunity to involve the government.”

He convinced Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru by saying it would be an “irony of fate that at the very commencement of our national government we do not send our team to defend our world title won and retained for nearly 25 years during the colonial regime.”

The gold of 1948 was especially significant as it was independent India’s first Olympic gold and it was won after defeating Great Britain 4-0.

Tata Sports Club medallists

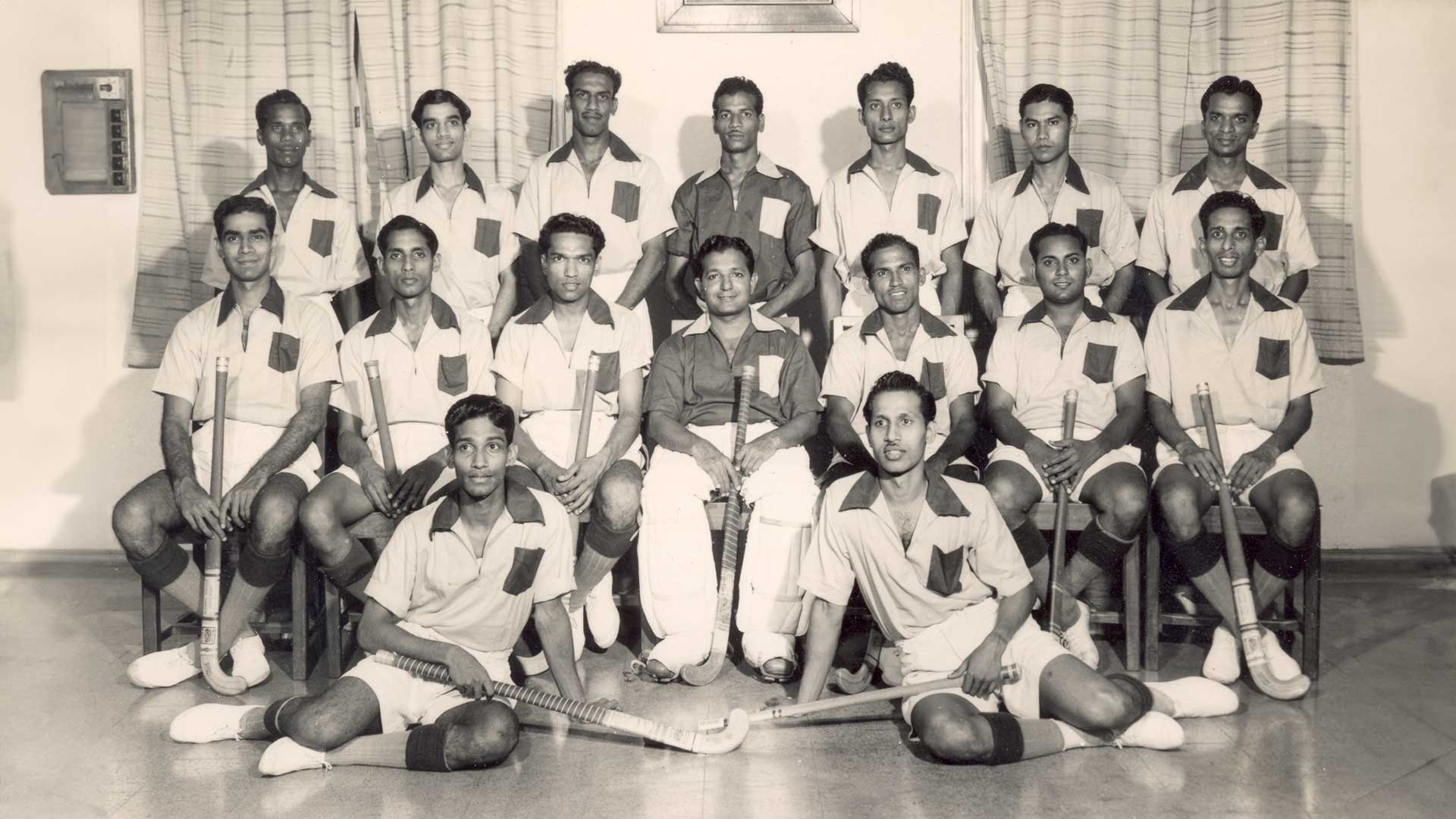

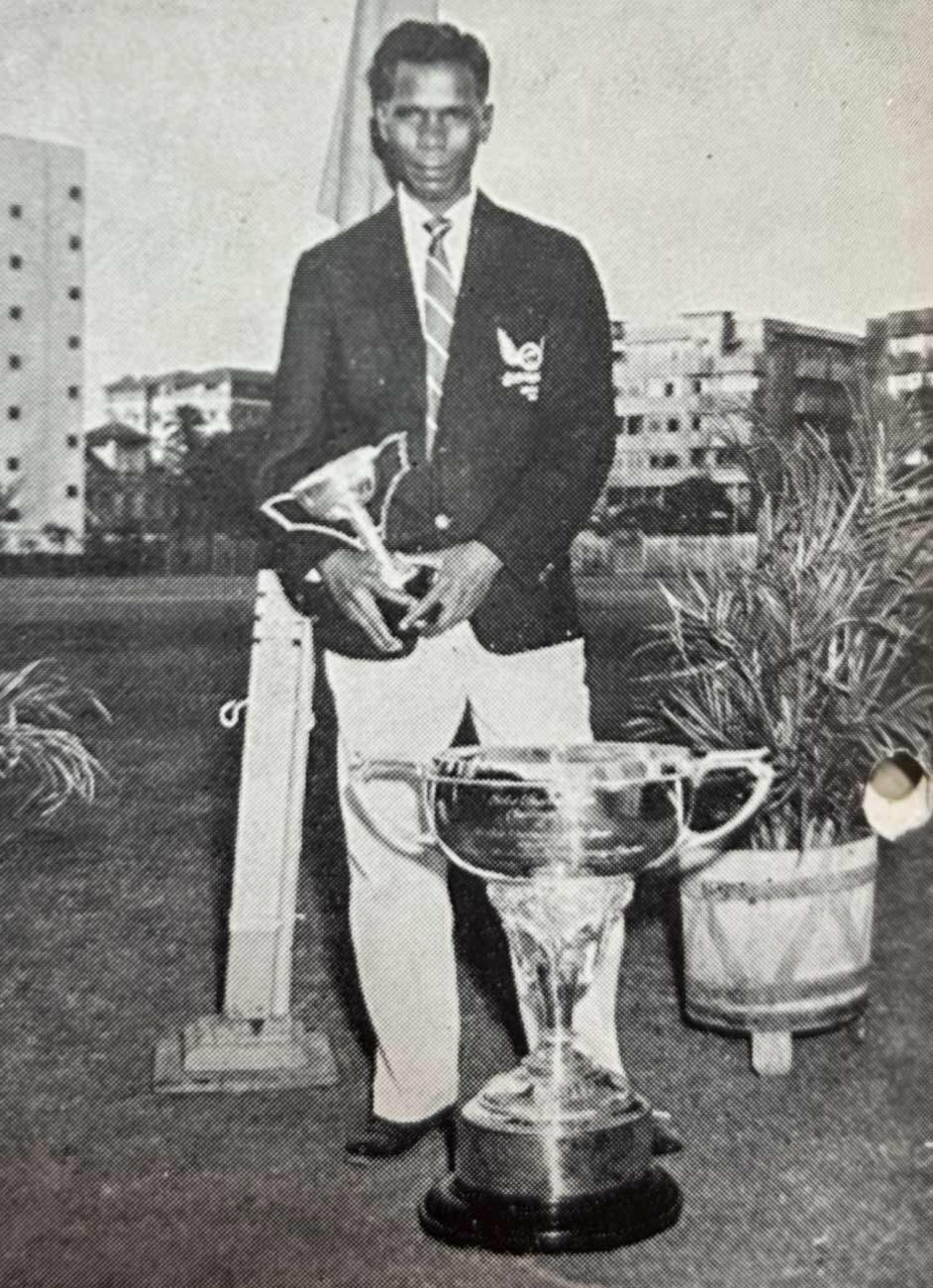

At least five players in the gold-winning hockey teams from 1948 to 1980, when India won her last hockey medal at the Olympics, were from the Tata Sports Club, which was established by JRD Tata in 1937.

Lawrie Fernandes and Leo Pinto were on the team that won the gold in 1948, while Randhir Singh Gentle was part of the teams that won the gold in 1948, 1952 and 1956.

Govind Perumal was part of the winning teams in 1952 and 1956.

Kulwant Arora was part of team that won the silver medal in 1960.

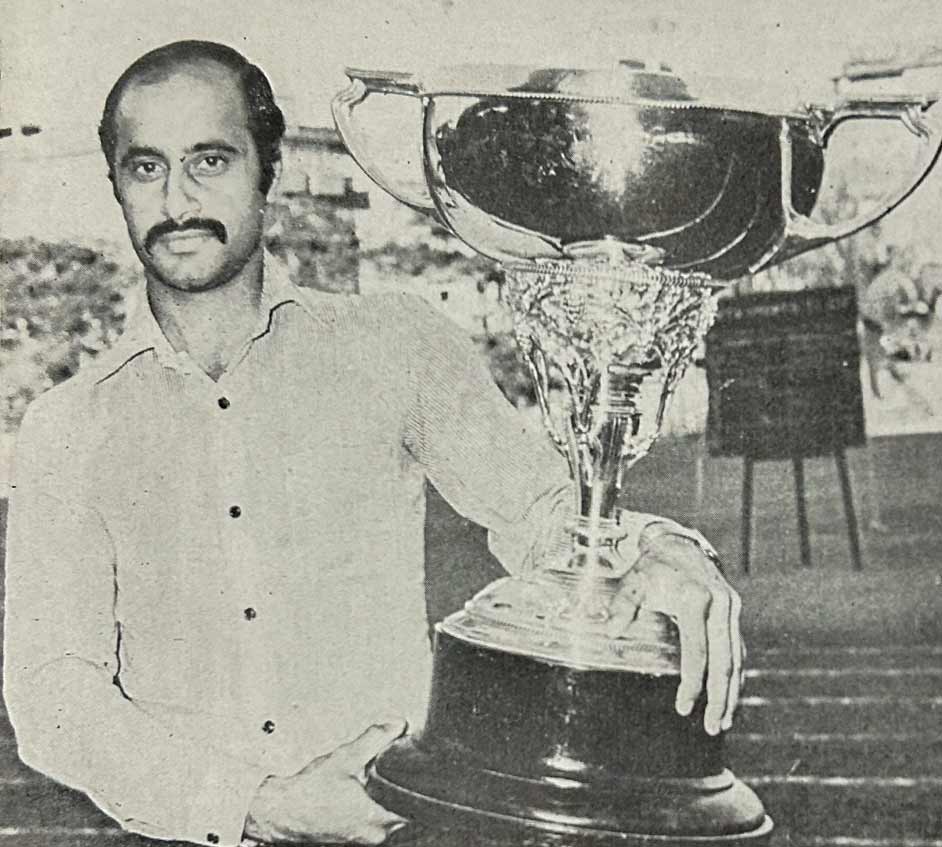

MK Kaushik was part of the Indian men’s hockey team that won the gold at the 1980 Olympics in Moscow.

Other Tata Olympians

The Tata group’s list of Olympic winners also includes:

- Gagan Narang, who was employed with Air India, when he won the bronze medal in the Men's 10 m Air Rifle Event at the 2012 London Olympics. He is a four-time Olympian (2004 to 2016).

- Marc Schneider, director of partnerships and alliances, Tata Communications, who competed in the 1996 and 2000 Olympics as part of the United States rowing team. The team won a bronze medal in 1996.

The Tata group now boasts at least 8 Olympic winners and 60+ Olympians (35+ of them from Tata Steel alone), who have participated in a range of events — football, athletics, archery, cycling, basketball, judo, boxing, shooting, etc.

As far back as 1948, the Tata Sports Club sent athlete Baldev Singh (who joined the Tata Textile Group in 1944) to Loughborough College in the United Kingdom for an advanced course in sports and physical training before he participated in the London Olympics in the same year. Several individual sportspersons have received similar support from Tata companies:

- Athletics: Lavy Pinto, Mercy Kuttan, Charles Borromeo, TC Yohannan, Bahadur Singh

- Archery: Sanjeeva Singh

- Hockey: Dhanraj Pillay (retired from Air India)

Some other notable names include Chuni Goswami (football), Edward Sequeira (athletics), Limba Ram (athletics) Dola Banerjee (archery), and Annu Raj Singh (shooting).

Tata employees have also been coaches for Indian teams and sportspersons at the Olympics. These include Dronacharya Award winning archer Purnima Mahato and hockey player Clarence Lobo.

Tata Olympians now

Star sportspersons who have emerged from Tata and represent India at the Olympics now include recurve archers Deepika Kumari and Atanu Das (both ex-Tata Archery Academy Cadets, both no longer with Tata Steel). The Indian contingent to the Rio Olympics in 2016 included Deepika, Atanu and TAA cadet Laxmirani Majhi. Deepika and Atanu also represented India at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021.

All eyes on Paris Olympics 2024

Recurve archers and TAA cadets Ankita Bhakat and Bhajan Kaur have sealed their place in women’s archery at the Paris Olympics. This will be their first Olympic outing.

Interestingly, this year’s entire Indian Women’s Archery contingent are products of Tata Archery Academy. Ankita and Bhajan (both present cadets / academy archers) and Deepika Kumari, who was trained at TAA since she was 13 (now with Indian Oil). The National Women’s Archery Coach Purnima Mahato is also from TAA.

—Monali Sarkar

Photographs courtesy Tata Central Archives