February 2020 | 1904 words | 7-minute read

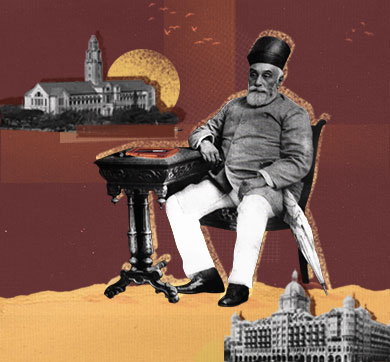

In his book, Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata: A Chronicle Of His Life, Frank Harris wrote, “He died as he lived, a citizen of Bombay…” Proud of his city and passionate about building a better life for its residents, Jamsetji undertook several ventures during the course of his life, which he believed would be beneficial for the city’s development, and its civic and cultural sphere.

Perhaps the grandest and most recognised of Jamsetji’s tributes to his beloved city remains the Taj Mahal Hotel. Standing tall and proud, overlooking the majestic Gateway of India, the hotel set up by the Founder of the Tata group has been more than just a witness to the life and times of this bustling city for some 110 years, its own existence often intertwined with the story and transformation of the metropolis itself.

When the hotel opened its opulent doors in 1903, it was a landmark on the Mumbai harbor (the Gateway of India became its neighbour 21 years later). With its awe-inspiring exteriors and luxurious interiors, including electric fans, elevators, Turkish baths and more, the Taj was every bit the dream that Jamsetji had set out to achieve: a hotel that Bombay would be proud of and which would attract tourists from across the world, a place where Indians would be welcome, in stark contrast to Watson’s Hotel, the city’s only five-star hotel before the Taj opened, which had an exclusive European clientele.

In fact, his assistant wrote, "As in the case of all his enterprises, he developed the idea (of the Taj) more out of patriotism and his love for the city, than as a commercial proposition, because he believed that Bombay ought to have a big hotel in the near future to cope with the growing prospects.”

While the Taj remains, to this day, the city's best-known edifice associated with Jamsetji, what is lesser known is his contribution to several other important projects and initiatives, among them the reclamation of land from the sea, his many real estate endeavours, the establishment of some of the city’s most famous clubs, his industrial ventures and his impact on the city's health and wellness. These had a far-reaching impact on the social, political and economic development of Bombay.

A passion for building

Building became one of Jamsetji’s chief hobbies. He saw huge potential in the city’s real estate. According to Harris, he had contemplated plans for the development of Salsette (Bombay island) since 1896.

Recognising the need for suitable and affordable accommodation for Englishmen of modest means, he built a block of 16 flats, called Gymkhana Chambers, in the Fort area of Bombay. As his financial status improved, he started buying significant portions of land in the city, especially in its northern parts, which he was particularly keen on developing. He wanted to build houses that could be rented out at affordable rates, so as to reduce the congestion in the city.

However, after a prolonged battle with the prevailing administration over unreasonable building fines in the area, Jamsetji abandoned the plan and concentrated, instead, on the task of reclaiming vast tracts of land from the Mahim Creek, between the suburbs of Bandra and Santacruz. “The chief advantage I am looking forward to is the improvement in the health of Bombay consequent on the reclamation of drowned lands, the malarial exhalations from which are at present carried to Bombay island by the north wind,” he wrote in a letter to the collector.

He purchased land on the islands of Mahad, Juhu, and Bandra, on each of which he built bungalows. Yet again, a protracted battle with authorities ensued, one that carried on well beyond Jamsetji’s lifetime.

Mills with a cause

The year 1887 saw Jamsetji make yet another important investment in the future of Bombay, when he acquired the sick Dharamsi Mills (then the largest in the Bombay Presidency) despite expert advice to the contrary, and rechristened it Svadeshi Mills, in line with his belief that to be politically independent India needed to be economically self-reliant. The solution, he was convinced, lay in the industrialisation of the country. The next few years were full of struggle as Jamsetji tried to turn the outdated mill around, working relentlessly on upgrading technology, even as an acute shortage of labour made matters difficult.

A lesser individual would probably have abandoned the venture, but Jamsetji made sure that Svadeshi Mills lived up to the promise he saw in it. Not only did he invest in new machinery and the latest technology, but he also introduced a slew of employee welfare measures that he was already offering his staff at Empress Mills. Thus, Bombay saw some of the earliest efforts at creating a better deal for its workers, including mills with improved light and ventilation, accommodation with decent sanitation, grains at cost price, medical facilities as well as pension and provident funds.

The fight against the plague

The book Taj At Apollo Bunder notes, “Early in 1896 dead rats began to be discovered in increasing numbers in the grain godowns (warehouses) near Mandvi docks. Then the godown coolies who worked there began dying, followed closely by grain merchants who handled the corn. By February of that year the mortality figures had reached 1,900 per week, with two out of every 10 persons infected dying of the disease. This was diagnosed as the bubonic plague.

“By 1899, the weekly mortality rate had exceeded 2,800. The plague devastated Bombay. Many thousands fled from the city, and work in the markets, the docks and the mills were brought virtually to a standstill. Business confidence had fallen to an all-time low.

“Attempts to carry out inoculations… continued to meet with widespread resistance, fed by rumours that the vaccine spread smallpox and leprosy. In order to combat the fears of the more superstitious members of their respective communities a number of leading citizens, JN Tata among them, enrolled as Justices of the Peace, accompanying the squads of soldiers, police and medical teams that went out to fight the plague and allay the public’s fears.

“JN Tata responded to the emergency with all his customary energy and intellectual curiosity. He made an exhaustive study of the subject of plagues and their causes and played a leading role in promoting the inoculation campaign within the Parsi community. Dorabji Tata got married at this time and his future father-in-law, HJ Bhabha, once happened to call at Esplanade House shortly before the wedding and found himself placed at the head of a queue of persons waiting to be inoculated—in order, so he was told by Jamsetji, to set a good example.

“After four terrible years, the ruthless measures that were being taken to combat the plague slowly began to take effect, although more than two decades were to pass before the city was entirely free of the infection. But it was against this background of the terrible visitation upon his city that Jamsetji suddenly announced his decision to build the Taj; a great hotel that would help restore the image of Bombay and attract visitors from abroad.”

Clubs and community

Jamsetji played an important role in the development of the city’s cultural and social scene and was responsible – directly and indirectly – for the establishment of Bombay’s most famous clubs.

He was by nature a clubable man, writes RM Lala in For The Love Of India. On his return to Bombay from Britain he started the British custom of establishing congenial clubs in the city. With his friend Pherozeshah Mehta he established the Ripon Club in 1883, to create a platform for political debate in the country. He was also closely associated with the Bombay Presidency Association, another leading political forum (this was established in 1885).

A firm believer in the benefit of athletics, sports and recreational activities, he took a prominent part in the establishment of the Parsee Gymkhana in 1885. He frequently attended the committee meetings, and to the end of his life was by far the largest contributor to its funds. With its charming, old-world aura, the Parsee Gymkhana remains a landmark of modern-day Mumbai.

The Founder also patronised a couple of other non-political clubs, including the Excelsior and the Elphinstone, important addresses in the social life of contemporary Bombay, and a precursor to the club culture that would become such an integral part of the city’s unique social fabric. Here he would spend many an evening playing a game of chowpator, engaging in lively discussions with other members.

The quest for clean energy

Perhaps one of the most significant influences he had on the betterment of life in Bombay was through his emphasis on renewable energy. At the time, Bombay was choking under the polluting refuse from mills in the city that were entirely reliant on coal.

As early as 1875, while surveying the falls of Jubbulpore, where the Nerbudda River rushes between the famous marble rocks, Jamseji envisioned harnessing the power of running water to generate clean, renewable energy that would be available to “run the tramways of Bombay, to supply as much electric lighting as may be required in Bombay, and to have a balance over for the supply of power in a few cotton mills, and sufficient for small local industries.”

Jamsetji did not see his dream of a hydroelectric plant come to fruition in his lifetime; a London-based company had obtained the licence to be the sole suppliers of electricity to the city. It fell to Sir Dorab to complete his father’s dream.

On February 8, 1915, while switching on the electric power to the first mill, and delivering a speech before then Governor of Bombay, Lord Willingdon, Sir Dorabji Tata said, “This is primarily an industrial enterprise: we hope that it will earn substantial profits for the shareholders. But it is something more than a money-making concern. To my father, the hydroelectric project was not merely a dividend-earning scheme; it was a means to an end—the development of the manufacturing power of Bombay.”

Providing a window to the world

Jamsetji’s pioneering spirit, along with his travels and experiences across the world, ensured that Bombay had the opportunity to see some of the latest inventions and practices of the Western world. If he brought the finest of European hospitality to the city, first at his magnificent Esplanade House home and then the Taj Mahal Hotel, he also delighted the people of Bombay when his carriages were fitted with rubber tyres (his were among the first carriages to move around the city without creating a racket).

As early as 1901, he also brought one of the first motorcars to Bombay. “He loved an ingenious device,” Mr Harris says in his book. “Though he cared little for music, he bought an electric piano for his home. When the cinematograph first appeared, he acquired one at once. His purchases were made, not so much for himself, as to let India know what was new in the great world across the seas.”

Jamsetji’s contribution to the city didn’t stop at just creating some of the city’s most iconic structures; it went much beyond into the many dreams he had for the city. Some of these were realised, some failed, but all of them were born of a great love for the city he called home.

Sources: Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata: A Chronicle Of His Life by Frank Harris; For The Love Of India: The Life And Times Of Jamsetji Tata by RM Lala, The Creation of Wealth by RM Lala