February 2020 | 1961 words | 8-minute read

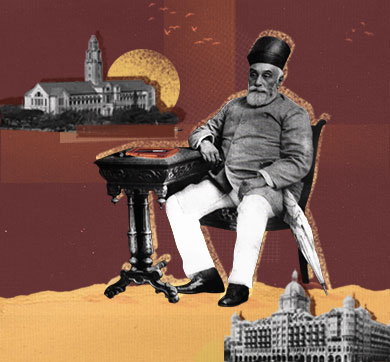

Long before India’s Swadeshi Movement kicked off in 1905, Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata had found his own ways to further the cause of ‘India for Indians’.

Committed to the advancement of his country, he believed that he would better serve India through the building and revival of her indigenous industries, than through political speech-making or agitation. To him, the industrial progress of India was to be the vindication of her growing aspirations, and of her demand for constitutional self-government.

Jamsetji was in sympathy with the Congress party, which was then in a temperate mood. Though he did not take an ostentatious part in politics, he decided to associate his firm with the development of a true Swadeshi movement.

The Swadeshi movement

Political consciousness was spreading by the 1880s, as the intelligentsia realised that the wealth of India was being funnelled to England making it necessary to patronise Indian goods. In the early 1900s, as the Swadeshi movement took root, it was believed that resources and industries of India should be developed by Indians themselves.

Before ‘Swadeshi’ became a political cry, Jamsetji had adopted the name for one of his mills. In 1886, he purchased the sick Dharamsi Mills (then the largest in the Bombay Presidency) despite expert advice to the contrary. He rechristened it the Svadeshi Mills to mark the beginnings of the Swadeshi movement. The mills would prove to be one of his most difficult projects requiring a radical overhaul. He scrapped the antiquated machinery, set up adequate lighting and ventilation and acquired subscriptions from shareholders, who were eager to invest in Jamsetji’s rising reputation as an industrialist.

But two years later, the mills failed to pay a dividend. Its early shipment of coarse yarn was rejected in the China market and the share price fell to a fourth of its initial value. With a remarkable demonstration of energy, acumen and sacrifice, Jamsetji put in his private funds and went to the bank for an overdraft. He had made a trust for his family and offered this as a pledge to the bank. He brought his best men from Empress and modernised machinery even though the mill was losing heavily. His efforts finally paid off a decade later, when Svadeshi’s yarn fetched the highest prices in the Far East market, and became one of the few that could compete successfully with yarn from Lancashire’s cotton mills.

Sir Dinshaw Wacha, who worked as Jamsetji’s manager at the Svadeshi Mills, and would later take over as president of the Indian National Congress, wrote in 1914: “Having been closely associated with the reconstruction of the Svadeshi for the first seven long years, the present writer cannot withhold his admiration of the indomitable courage, business capacity and tenacity of purpose Mr Tata displayed in bringing up the institution.”

The Indian National Congress

According to RM Lala, when Jamsetji found himself in England at age 25, was when his views and opinions were shaped in the company of men like Dadabhai Naoroji (one of the founding fathers of the Indian National Congress, known as the ‘Grand Old Man of India’) and Pherozeshah Mehta, over Sunday meetings at Naoroji’s home.

But while Jamsetji sympathised with Naoroji’s views, nurtured a certain closeness with the Indian National Congress and was even present at its first session in 1885, he believed that political independence would be meaningless without economic self-sufficiency.

Dinshaw Wacha wrote that Tata was ‘as keen and robust in matters political as he was courageous and enterprising in matters industrial’. But he did not take an ostentatious part in politics. Speeches and banquets had little fascination for Jamsetji. For one so interested in politics, he exercised the greatest self-restraint in putting forward his views to the public, but no gathering was considered to be really representative unless he gave it his support.

In the biography of Sir Pherozeshah Mehta, who played a leading part in the initiation of the INC, Jamsetji’s name occurs but twice, and then not in that connection. Yet years later, at the unveiling of the Tata memorial, he pointed out that from the first Jamsetji supported the Congress’s endeavours towards India’s freedom and remained a member of it to the end of his life.

He gave freely both of his time and money to the Bombay Presidency Association, which provided the local machinery for the Congress. ‘The current notion,’ said Sir Mehta, ‘that Mr Tata took no part in public life, and did not help and assist in political movements, was a great mistake. There was no man who held stronger notions on political matters, and though he could never be induced to appear and speak on a public platform, the help, the advice, and the co-operation which he gave to political movements never ceased except with his life. And the proof of this statement lay in the fact that Mr Tata was one of the foundation members of what might be called the leading political association in the Presidency — the Bombay Presidency Association.’

Jamsetji held strong views, and when, on one occasion, a friend thoughtlessly said to him, “You can have no concern with the Congress, you are not a native of India,” he retorted, “If I am not a native of India, what am I?” For he was an Indian first, and a Parsee afterwards. He was in the fullest sympathy with the aims of Congress, as he knew it, when it was working for self-government by constitutional means.

His faith in India’s future was coupled with a desire for her political progress. He had great ideals of the scope and duties of government of whose shortcomings he was by no means a silent critic. Steeped as he was in philosophic radicalism, Jamsetji welcomed every reform, and he would seethe with indignation at what he deemed an injustice. According to Frank Harris, “He condemned the sycophants who concealed those grievances which galled his countrymen, but he had little sympathy with malcontents who had no practical policy to put forward for the betterment of the country. He was, himself, a practical reformer, sociologist and philanthropist.” J.E. O’Conor noted, “He never made himself prominent as a politician, leaving public affairs and speech-making to others, but he held strong views, and was intensely patriotic.”

Protecting Indian enterprise

In his biography of Jamsetji Tata, Frank Harris noted that Jamsetji had an excellent head for figures, was a sound authority on currency problems or the fluctuations of the exchange, and the manipulation of the bank-rate. As such, any measure which tended to disturb India’s economic stability would soon call forth a protest from Jamsetji. This meant that he fought several battles with the British in the interest of Indian business and enterprise.

On tariffs that affected the competitiveness of Indian cloth: In 1894, the government imposed a duty of 5% on all imported goods barring cotton yarn and fabrics to protect the British cotton trade. Jamsetji attacked the ‘false imperialism’ that considered the benefit of tariffs only for the Englishman and not for the empire. Despite British resistance, around 1897, Jamsetji started an inquiry into the profits of the past 10 years, which would serve as a guide to those who desired the repeal of the excise. He also spoke up against textile machinery manufacturers in England who charged him and other Indian mill owners more than they did their British customers.

On shipping rates that discriminated between Indian and British goods: Jamsetji’s Svadeshi Mills was one of the few to make fine yarn and compete successfully in the Far East with yarn from Lancashire. The prime shipping line, P&O, was charging higher freight rates for Indian goods than for British goods. To break their monopoly, Jamsetji started the Tata Line, a rival shipping line with the Japanese, to get the rates reduced so that India could compete with British textiles in the Far East. What ensued, in Jamsetji’s own words, was a ‘war of freights’. The Tata Line folded after a while due to unfair trade practices of P&O and the inability of the Bombay cotton mills to recognise that Jamsetji was engaged in a national struggle and not merely another business. RM Lala notes, “Had the government done something to ensure that unfair trade practices were not allowed to thrive, there is no doubt that the Tata Line would have heralded the beginning of a modern Indian shipping line a quarter of a century before Scindia Shipping was established.” Tata Line did end up becoming one of the founding stones of India’s trade ties with Japan.

On levies that inhibited the development of Bombay’s suburbs: During the reclamations of 1865, a series of building fines had been imposed upon undeveloped land, and these were heavy enough to hamper anyone who attempted to cope with the housing problem. For years Jamsetji tried to obtain a reversal of this policy.

He also planned the provision of houses in the undeveloped districts at a moderate rental to relieve the city’s congestion. It was already recognised that he 'had done more than any single human being to provide Bombay with building fit to live in’, and there was a cry of disappointment when it appeared that his schemes were thwarted by what seemed an obscure and unreasonable tax.

‘The growth of towns,’ Jamsetji wrote, ‘must, I need scarcely repeat, add far more to the sum of national life and national prosperity, than anything which, in the shape of an immediate addition to the revenue, can possibly be hoped for by the system of building fines.’

On bimetallism and the Indian currency: Bimetallism – the use of both gold and silver as legal tender – was discussed by every man who took an interest in the financial affairs of the world… India, with her bimetallic standard, suffered from continual fluctuations in the value of the rupee, due to the ever-changing relations of the ‘gold price of silver’. In 1893, the Indian mints put an end to the free coinage of silver, and the government endeavoured to stabilise the value of the currency.

In 1894, Jamsetji plunged into this controversy, by writing a letter to the Statist. He was alarmed at the inevitable increase of India’s indebtedness to her foreign creditors, which was a clear loss to his country, and to the Empire Cotton. The only important Indian manufacture, Jamsetji said, would be ‘most seriously crippled’. The new legislation gave to the Japanese merchant a great advantage. ‘Her competition,’ he said, ‘has already robbed India of the Japanese yarn trade. It may now cut us off from our best customers, the Chinese.’ In addition to hampering the foreign trade of India, he also noted how it would adversely impact the agricultural class in India.

Sources: Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata: A Chronicle Of His Life by Frank Harris; For The Love Of India: The Life And Times Of Jamsetji Tata by RM Lala, The Creation of Wealth by RM Lala

Photographs courtesy Tata Central Archives